- web

- css

- react

- styled-components

The internet changed rather fast, both on its adoption, usage, and technology behinds it. If we look at web development just for the last 2, 5 or 10 years, we can easily be tricked they’ve come from completely different worlds.

I remember the first steps I’ve made from being just a designer and to adventure myself on some html and css. And it seemed pretty magical to me — maybe because I’ve had plenty of mentorship and guidance.

— Me, just a couple of hours after learning how to apply background-color to a divCSS is pretty easy, right? It’s just applying some style rules to a specific element, what could go wrong?

Maybe I was just naïve about the scale things might get on the web, or I hadn’t lost enough nights fighting bugs at that time.

Not that I was entirely wrong, nor does it means that handwritten stylesheets it’s not a way of writing styles anymore. It’s just that my concerns at that time were totally different from what developers face in their everyday job today.

For example, a coworker said he was struggling to build a grid layout with the current tools (flex-box had just launched), and every css library limited him on having a single fixed gutter width — percentage or pixels — on every breakpoint.

Back then I wasn’t working with frontend yet, but it wasn’t that hard to write my first own library that supported it while being backward-compatible with the Bootstrap API, and it only took roughly 50 lines of stylus code.

I’ve used mostly that grid system for basically every static website I’ve developed at that time. And that was the moment I’ve realized how important it is to separate concerns and think deeply about APIs — even when you just copy what’s mainstream at that time, to understand different approaches, it really helps you to build abstractions and to extend them as you need.

Let’s get back to Bootstrap. I’ve never been a fan of it — and mostly used on already running projects. But it certainly paved the way to nicer things, it wasn’t the first, but certainly one of the biggest CSS frameworks of all time, I’m pretty sure every web developer used it at least once.

Laying grids on Bootstrap usually looks like this:

<div class="row"><div class="col-xs-12 col-sm-6 col-lg-4"><p>First</p></div><div class="col-xs-12 col-sm-6 col-lg-4"><p>Second</p></div></div>

The key point here is on how concise and expressively one can write and know exactly what it would look like. It’s like that unix philosophy axiom: Do One Thing And Do It Well. Defining a single purpose for the column div makes it clear what it does and easier to reuse everywhere without worrying about some obscure inheritance behaviour or having to write it every time.

That was one of the greatest abstractions Bootstrap brought to the mainstream, and perhaps the most copied and used feature of it.

The most famous paradigms on these new tools are composition and thinking with components, but other perks are often overlooked for dealing with styles.

Besides being easier to pass values between markup and styles, we now can declare a unified set of tokens in a theme and use it in place, and be confident they are producing the result we wrote.

Although the tools have changed and, in a sense, are now much more powerful, some principles we developed and used back then may still be valuable or have new meaning on current workflows.

It’s now easier than ever write our own design systems, and have a direct way to cross the lines between styles and markup when we need, and write our own rules and themes with JS functions at run time, and not only compiled SASS or CSS variables. And all of this is awesome — and I use it every day including at this website.

All this power — or at least these new ways to apply styles — might have blinded us and lead to a really short Icarus’ flight. It’s not unusual, to step into a recently built project that’s set up with all the nice things™, JS frameworks et al. but struggles with some basic things we sorted out long ago, even with plain CSS.

And again, I’m not advocating on a single way to solve all problems, each project has its own reality and requirements. But if, for example, the project is designed with a rigid column-grid layout, we shouldn’t fight it and keep creating every single content block style again and again by hand. We haven’t done this back then, and we certainly won’t need to do it now, we have better and smarter tools, let’s use them.

// Now let’s rewrite that grid with styled-componentsconst Row = styled.div`display: flex;flex-wrap: wrap;margin: 0 -16px;@media (min-width: 768px) { margin: 0 -24px; }@media (min-width: 1024px) { margin: 0 -32px; }`const Column = styled.div`width: 100%;padding: 0 16px;@media (min-width: 768px) { width: 50%; padding: 0 24px; }@media (min-width: 1024px) { width: 25%; padding: 0 32px; }`const GridWithStyled = () => (<Row><Column><p>First</p></Column><Column><p>Second</p></Column></Row>)

You may say that this was totally non-sense, we’ve hopped from a single line that is flexible, readable, easy to change, and therefore can be used anywhere in the code, to a bunch that is pretty specific to a single-use case, that generates a lot of overhead to read and maintain, and it doesn’t use any amazing feature the ecosystem has to offer.

Yep, it is totally non-sense but it is pretty normal to stumble on such a thing these days. It solves the problem, but in the long run, it might start to hurt some fingers to write the same things over and over.

If we take a look on the other side of the ring we can clearly see another tribe being formed: the prop junkies. They are the exact opposite of the last example, and they propagate the message that every layout can be written with less than a dozen components filled with style-related props. They are descendants of utility-first CSS tribes — tailwind for example — and their most famous prophets are rebass and styled-system.

const GridWithRebass = () => (<Flex mx={-2}><Box width={[1, 1/2, 1/3]} px={2}><Text>First</Text></Box><Box width={[1, 1/2, 1/3]} px={2}><Text>Second</Text></Box></Flex>)

Wow, that was really different, wasn’t it? These approaches solve most of the styling directly in the markup, leading to fewer lines of CSS. It’s a nice approach, it uses the maximum “extendability” and there are many awesome libraries being built upon these ideas too — eg.: Github's Primer components.

Yet, for an outsider it may be a little overwhelming to process and clearly understand what is going on, especially when there are multiple layers of <Box/> nested into each other. It also leaves us with the burden of declaring some fine detail every time — like the margin/padding on the grid example above.

And if we look closer, we just changed where we’re repeating ourselves — of course, both examples can be written in a much cleaner and reusable way, and that’s exactly what we’re about to discuss.

Most projects I’ve worked on the last years — from static marketing websites to more complex applications — fall into one of that 2 ways of writing CSS, because at some time it made more sense to the project, or the team was more used to it.

But, what if we could pick the best of both worlds, it would probably be more productive and future-proof, right? A way that could be easily extended to solve new challenges and needs, while keeping our sanity while working with it.

I believe the way out is really aligned to one of react’s greatest laws: being declarative. Not only with the code (markup and/or styles) itself, but with humans reading it. Mix that with the unix philosophy and we would have something like that for our grid example:

<Grid.Row><Grid.Column xs={12} sm={6} lg={4}><p>First</p></Grid.Column><Grid.Column xs={12} sm={6} lg={4}><p>Second</p></Grid.Column></Grid.Row>

It kinda feels like home again, you can easily read it, there’s no CSS to be writing every time, and the things that should be fixed (like gutters on this example) are safely stored on our theme, so we don’t have to remember to declare them every time.

Behind the hood, these grid components can be written in a really reusable and concise manner, they only have to map their environment and output their rules, or as some call it: Style as a Function of State.

If we look closely enough, the only difference is the use of props instead of class names, but behind the hood, some functions are using the declared values, and there’s something taking care of the gutter for us too.

From this example we can think about 2 things that help us create these building blocks:

Theme: design tokens and UI state that you shouldn’t need to be specifying every time (dark mode context, color palettes, sizing scales, typographic scale, etc)

Props: will act as our external API, or the arguments, to build slightly different outputs, with the same component (number of columns to fill, typographic style to use, and so on).

As mentioned above, we can cross the theme and props to build a readable component. As one can imagine, I began just using this technique for grid components, but found use for it on many scenarios, on different projects.

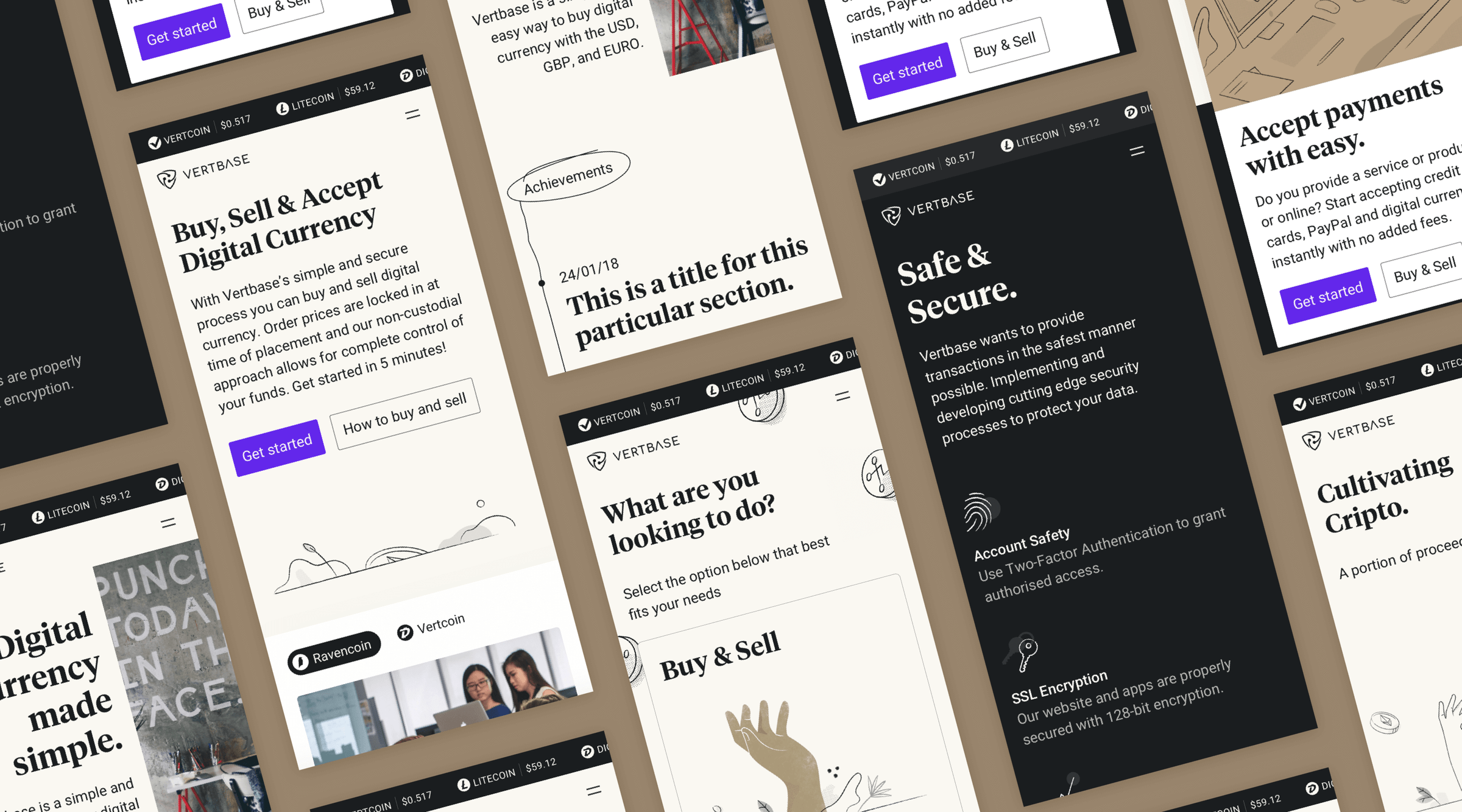

On Vertbase project I was handed the beautifully crafted screens, alongside a really strict style guide, containing the grid, the typographic scale, colors, and basically every other design token I would need for the project.

Before starting laying the markup, I’ve put everything on the App’s theme, then I started seeing the breakpoint-value pattern repeating itself.

All the components on the website were unique, they shared no single inheritance and there were no “global” headings or paragraph size, for example, so making a component mapping typography styles on each breakpoint really made sense and cuts thousands of lines of code.

Composing with just 3 basic components: Grid, Text, Spacer, I could develop most of the site in record time, without repetition, breaking the strict style guide, or overwriting edge cases.

and another mind-blowing fact of this approach is: no component was bigger than 15 lines of styled declarations.

Although most of this article was written using the react/styled syntax, some of these ideas can be achieved with CSS preprocessors. But, in my opinion, it would be a much greater work and possibly not as flexible as we might want or need.

After working with some projects adopting this pattern, I’ve built a library called etymos — it’s currently based on styled-components — although I’m planning on releasing an agnostic or emotion version too — and really lightweight (1.2kb).

import { mapBreakpoints } from 'etymos'// theme declaration (passed to <ThemeProvider/>):// different from other libs no standard shape is enforcedconst theme = {typographicScale: {caption: { s: 14, l: 20, c: 0.0 },body: { s: 16, l: 23, c: 0.0 },},}// create Text component:const getTypeStyle = name => ({ theme }) => {const { s, l, c } = theme.typographicScale[name]return [s && `font-size: ${s}px;`,l && `line-height: ${l}px;`,c && `letter-spacing: ${c}px;`,].filter(x => !!x)}const Text = styled.div`${mapBreakpoints(getTypeStyle)}`// example of the <Text/> component in use:<Text xs='caption' md='body'>Text use the `caption` style on `xs` breakpoint upand `body` from the `md` breakpoint up</Text>

Other examples can be seen for this exact site for Grid, Text and Spacer components.

While there are infinite ways to get you there, this one already serves me well, and it may be useful or inspire you to build something even greater.

Any doubts, questions, or further ideas please open a issue or a pull request on github.